Preserving the Past on a Decentralized Future

Rick Prelinger is all about contradictions. He’s a 72-year-old archivist, but his shock of white hair is dyed a cyberpunk blue. He’s a historian who is desperate to expand public access to rare materials — and also knows that the process of sharing fragile items can sometimes end up destroying them. And, like any good collector, he’s obsessed with the ancient and the obscure… yet he’s tuned in to next-generation technologies.

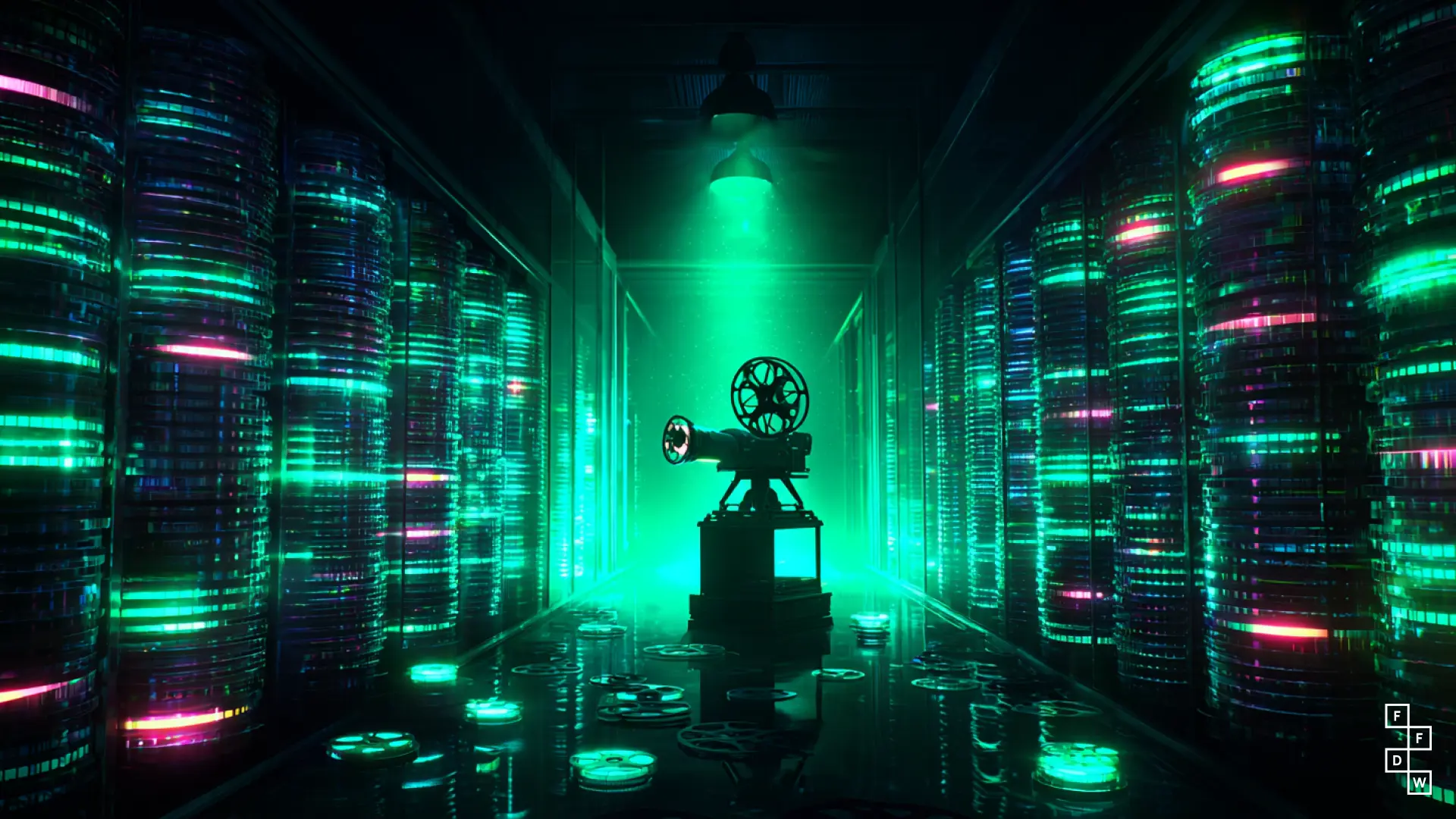

Here’s an example: We’re on the upper floor of a sprawling warehouse outside San Francisco where his immense, generational film preservation project, the Prelinger Archives, is working to scan thousands of ephemeral movies from its collection — and then upload them to a warren of decentralized digital storage, organized and managed through Filecoin.

“There is push and pull, and there are protocols,” he says with a grin. “But onchain is the next development. It's the next stage of making sure that material is safe and material is available.”

Since 1983, Prelinger has been obsessively collecting video from just about every place he can, particularly those that get lost or ignored: old advertising reels, home movies, amateur films. Beginning in 2000, the Archives have been putting that material online, mainly in close collaboration with another Bay Area institution, the Internet Archive. And then in 2023, things went even further, when Filecoin Foundation for the Decentralized Web (FFDW) made a grant to the Prelinger Archives to help it make those videos available through its decentralized technology.

That’s made it possible not just to digitize what’s already in the collection, but to work with new organizations to help them store and share their own history.

“It could be somebody in the community who has a home movie collection. It could be the Filipino American Historical Society. It could be the Mission Media Arts Collection… It could be the Center for Asian American Media. Our priority here is to daylight material that represents underrepresented people and underrepresented communities, because there's such a great demand for that right now.”

Underrepresentation has been part of the script from the very beginning. By design, the Prelinger Archives focus on the kind of video that often gets tossed aside, junked, or just plain forgotten. Some of the films they get hold of haven’t been watched for decades, and some have possibly never been seen. But to Prelinger, these strips of film hold precious opportunities for viewers, whether it’s the chance to witness a city’s streetscape from 75 years ago in the background of a promotional short, or finding footage of a Native American ceremony that somebody inadvertently caught on 8mm home video in the 1960s.

Inside the facility’s network of rooms, he guides me through the process that a piece of film takes to make it from the bin to the blockchain. I watch as the team works in a painstaking production line. One member of staff diligently takes film from a canister and carefully examines the strip inside, cutting it, cleaning it, and readying it for scanning. Sometimes, you open a tin and the material inside has decomposed, points out archivist Jennifer Miko, melted or vinegared. But this one’s OK, she says: crinkly on the edges but probably salvageable. I know how it feels.

Once the film has been successfully prepped, it’s passed to another expert who feeds it into one of the project’s scanners, a byzantine assembly of wheels and knobs and cameras and recording equipment. The machine’s wheels spin backwards and forwards, projecting and capturing the visuals and sound in a stop-start dance (Every 5,000 frames, the machine stutters and checks to make sure everything’s still in sync.) On a nearby screen, we watch the output that’s being pulled through in high definition: this one’s a developmental psychology film of young boys from the 1950s. And from there, staff add metadata, tag the video, and run quality control checks, before moving it to physical storage and, eventually, onto the internet and the blockchain.

Over at the Internet Archive — another recipient of a grant from Filecoin Foundation — the chain is also part of the picture, although different material creates different complications.

Mark Graham, director of the organization’s Wayback Machine project, has responsibility for the Internet Archive’s more forward-looking work. He says copying data to decentralized technologies is one of several bets the organization is making to future-proof itself: to ensure the long-term security of the vast troves of records it is collecting, which stretch from websites to software to books.

“We spend a lot of time looking at possible futures, and the blockchain is one of them,” he says, “But it’s still more experimental, and so we’re exploring.”

Exploratory, yes, but the end goal is clear: find new ways to ensure that information can be available forever, that stop it from being eroded or erased. Sometimes that’s just because of natural attrition or a lack of attention, similar to the problems Prelinger sees. Sometimes, however, it disappears through deliberate deletion. Since November 2024, for example, the Archive has been working around the clock to capture and share as much information as possible from the US government’s huge libraries of documents and information, even as the current US executive deletes material from previous administrations.

With the integrity of information facing new types of threat, Graham says it’s time to see what options the chain has to offer.

“We generally think decentralization is good and has benefits, and we’re seeing how it might be realized,” he says. “But it’s a game with many winners.”

There are detractors, of course, and challenges for all archival projects. One of the issues both teams face is scale. The Prelinger Archives collection stands at maybe 40,000 videos (on top of 60,000 that were already donated to the Library of Congress), and it’s producing around 18 terabytes of video each week — too much for their current unoptimized decentralizing process. So right now, the team is producing smaller, more usable files for decentralization and keeping the higher-resolution originals elsewhere.

If that scale makes your eyes water, then the Internet Archive’s challenges might pop them straight out of your head. Graham says the organization deals with around a billion items a day and currently hosts around 175 petabytes of material across all its formats.

Still, the march of technology suggests decentralizing will get easier over time — or at least cheaper: Prelinger says that when he first started working with the Internet Archive, it cost about $100 to digitize a minute of footage. That number is drastically lower today.

But why do it? Well, everything needs a backup, he says, and “lots of copies to keep it safe.”

In reality, though, it’s less about backups for the present and more about creating a gift for posterity. These aren’t our materials, says Prelinger, and they shouldn’t be ours to gatekeep: putting them on the decentralized system is the next step in their liberation.

“You find yourself in collaboration with people all over the world, many of whom you will never know,” he says. “We've enabled hundreds and hundreds and thousands of projects; our material became canonical. While I'm the first person to argue for attribution, there's something that happens when your collection, when your content, becomes part of infrastructure. History needs to be infrastructure, like water and air.”

“The idea of getting stuff on the chain and letting it float around through the world and be available to everybody? That’s the highest destiny that an archive can aspire to… when you give up control.”

Bobbie Johnson is a media maker, editor, strategist and entrepreneur with more than two decades of experience in the US and UK. He was most recently editorial director at the Steve Jobs Archive. Prior to that he held roles at MIT Technology Review, The Guardian, and Medium, and helped start award-winning publications Matter and Anxy.