In today's digital landscape, free and open source software has become more ubiquitous than ever. Unfortunately, at the same time, it appears extraordinarily far from achieving its stated goals of giving users access to and control over code.

This paradox is rooted in the fact that while free software has democratized access to “code at rest” and enabled efficient collaboration between software makers, the operational challenges of running code are now playing the same role restrictive licenses once did — creating lock-in and barriers to entry. Cloud companies such as AWS may not control the code for technology like Kubernetes, but they do control the ability to use it in practice at scale.

To overcome this operations barrier and achieve its goals, free software must begin to make the operational power to use the code as accessible as the code itself. The path forward looks very different for enterprise software and end users, but for both the decentralization of running code plays a vital role. Free software won’t fulfill its goals until we can decentralize the role of the server.

Where Free and Open Source Software Began

In the beginning of the age of the personal computer, it was proprietary licenses that controlled access to code and software development tools, but as software grew in complexity that changed. Software began “eating the world” and to address the complexity of real-world use cases and planetary scale, software had to increase in complexity, and manage that complexity through increased efficiency. Free and open source software, whose aim is to ensure users’ freedom, control, and sovereignty over code, emerged victorious as a tool for efficiency.

Specifically, free and open source software let software projects collaborate globally on 90-95% of their codebase — sharing cost and risk — while focusing precious in-house engineering efforts on the 5-10% of their codebase essential to their core product and value proposition. Today, you will find almost no modern software products made purely from proprietary code. In the degree of adoption and democratizing access to software development, free software succeeded beyond its wildest dreams.

However, in terms of bringing users sovereignty there was a problem: the same increase in complexity of software stacks and scaling requirements that compelled software companies to adopt free and open source software also created a dramatic increase in the complexity of deploying software. By the mid-2000s, GNU/Linux and the web stack had emerged as an off-the-shelf way to quickly deploy software on the web, to the world. But as complexity increased, the ability to deploy software on a GNU/Linux stack at scale became much more difficult, and companies like Amazon Web Services (AWS) entered the market, competing on operational excellence. Services like AWS and Heroku could ensure your company’s basic Linux-based services were running, so your team could focus on code and product.

In terms of technological sovereignty, this was a shift backward to the era of mainframes, where all code ran on hardware controlled by a few large providers. Dependence on cloud services for operations created a fundamental shift in the degree to which free software could succeed at its aim of giving users control and sovereignty. Free and open source licenses for code would no longer be enough.

Where Free and Open Source Software is Now

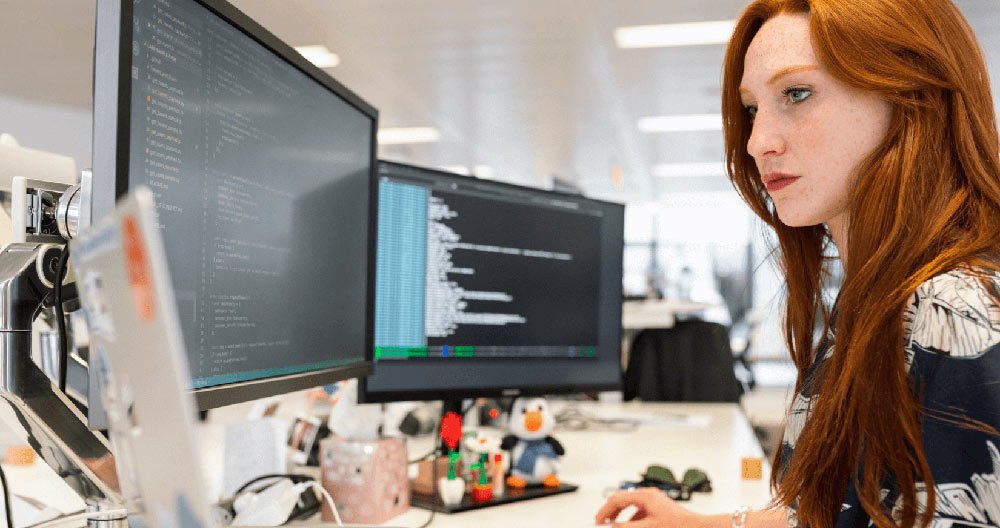

Ten years later, the ability to deploy free software-based apps to actual users is (for practical purposes in most cases) entirely dependent on cloud services, because the knowledge, experience, and practices for how to do so is locked up within these organizations. Cloud services such as AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud enjoy such significant marketshare not because they control the code for technologies they deploy (tools such as Linux, Postgres, and Kubernetes are free and open source software) but because they control the ability to use it at scale. Most engineers don’t even learn these tools directly anymore; they simply learn to turn to a cloud services company, purchase the correct service, and make it work for their needs. The power to operationalize code is creating the same lock-in and barriers to entry that software licenses once did.

Unraveling this problem will require distributing operational power with the free and open source code itself. This will require a mix of practices, from straightforward approaches like "GitOps" (including DevOps tools and scripts in one's Git repository) to more qualitative work like identifying and eliminating any barriers to becoming proficient in operationalizing free software tools. This shift will be essential in breaking free from the control of cloud companies and ensuring that organizations have the capacity to fully access and leverage free software.

The Solution for End Users: Decentralization

While solving the problem of distributing operational power is a complex undertaking for enterprise users, for end users it is much simpler: software must not require servers at all. Most users don’t have servers, so any software that requires a server will inherently rob users of the ability to operationalize the code and achieve sovereignty. After all, if free software code requires something most users do not possess, users cannot operationalize that code; it will remain a mere proof of concept until some company operationalizes it, creating a relationship where users depend on that company. Almost no one runs their own email server despite abundant free software code; instead they use Gmail and depend on Google for that. Consequently, the key to solving this problem for end users lies not in GitOps or documentation but in shipping pure peer-to-peer applications that do not require any server or the knowledge of how to use one.

This is not as difficult as it seems, and it has become much less difficult given recent improvements in the state of the art. The world has two decades of filesharing tools like BitTorrent, and over a decade of Bitcoin clients. Both are excellent examples of peer-to-peer applications that connect users without servers, delivering both code and the power to operationalize that code in a single package. My own project, Quiet, uses tools like libp2p and IPFS (developed for blockchain networks like Ethereum and Filecoin) to build a no-server-required alternative to team chat apps like Slack and Discord. Building fully peer-to-peer applications used to be seen as an unrealistic pipe dream, but no longer.

Decentralization: Where Free and Open Source Software Must Go

Decentralization can play a pivotal role in democratizing the operationalizing of software, both in the enterprise setting and for end users. Although decentralization is not a silver bullet, decentralized tools like Ethereum and Filecoin combine code and operations in sophisticated, incentivized networks built on open-source code. These networks offer the potential to create a more level playing field in the world of software, allowing individuals and organizations to harness the full potential of free software.

For example, Ethereum's smart contracts and decentralized applications (dApps) provide a framework for creating applications that are not dependent on a central authority. This enables businesses and end users to build and utilize software that is both transparent and secure. Similarly, Filecoin's decentralized storage platform allows users to store and retrieve data without relying on centralized services, giving users more control over their information.

By embracing decentralization, the free software movement can evolve to overcome the paradox of losing while winning. By incorporating the operational power to use the code within the code itself, free software will empower enterprises and end users to take full advantage of the code they have access to. Decentralized networks and platforms, such as Ethereum and Filecoin, can help usher in this new era of democratized software, breaking down barriers to entry and ensuring that everyone can benefit from the innovation and collaboration that free software enables. Peer-to-peer applications like my own project Quiet, built on similar building blocks but without the need for global blockchain networks or money, bring these tools to communication and social media.

Conclusion

The paradox of free software is a pressing issue that must be addressed if we are to fully realize the potential of open-source technology. By shifting the focus towards incorporating operational power within the code, and embracing decentralization as a means to democratize software operationalizing, the free software movement can overcome the current challenges it faces. This new era of free software will not only empower enterprises and end users, but will also foster a more open, inclusive, and innovative digital landscape for all. Decentralization is the next logical step for free software