Creating Human Records that Stand the Test of Time

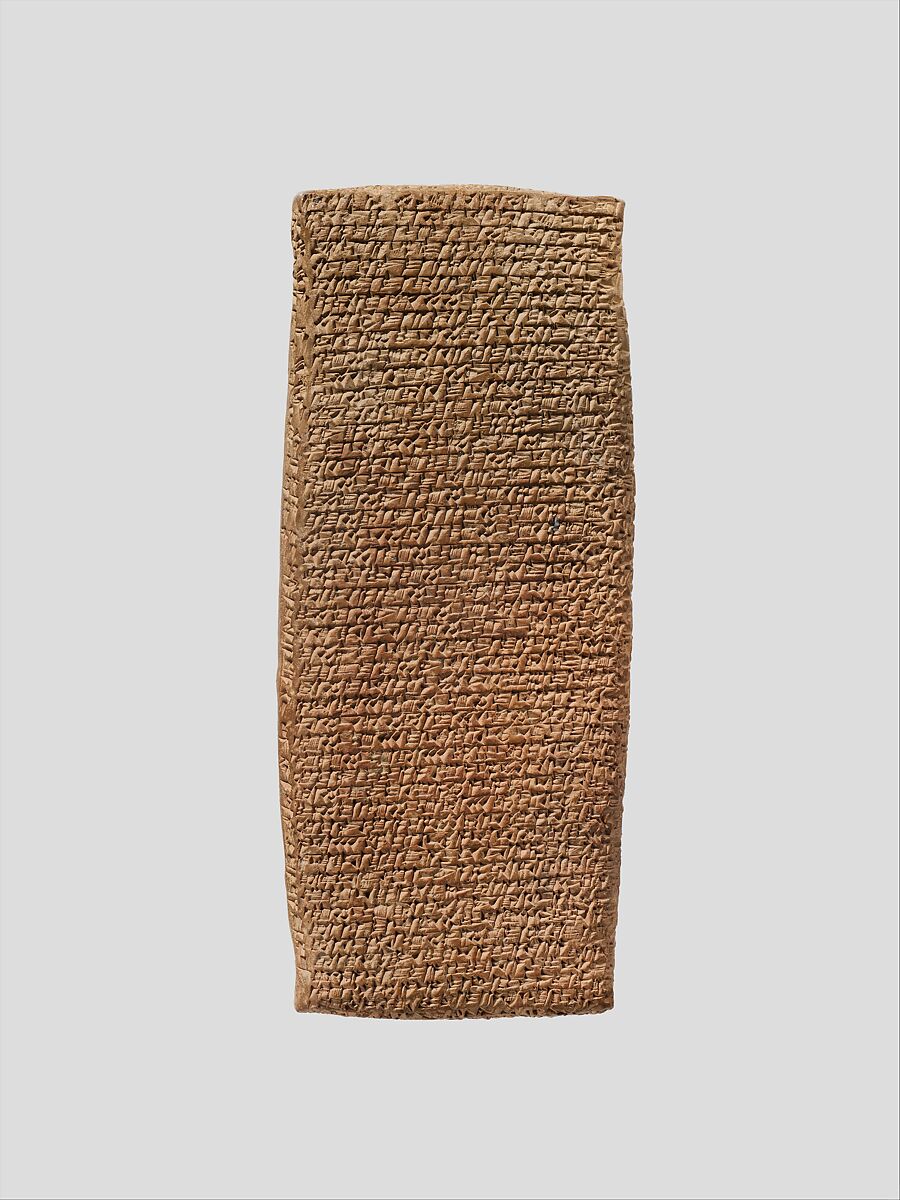

As business rivalries go, the story of Suen-nada and Ennum-Ashur was pretty routine. They both claimed ownership of valuable intellectual property, wrestled over control of accounts, and accused each other of theft.

Their case went to court. Witnesses were present. Testimony was delivered and became crucial evidence.

A fire burned down their Assyrian colony in 1836 B.C., but a record of their testimony survived and is now available for review at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

We know about the trial because, thousands of years ago, the world’s most advanced technologists figured out how to use a crude implement to etch markings into stone and clay. This data storage breakthrough would be used to record crop yields, trades, weddings, births, deaths, wars, legends, and other data that was critical to evolving human civilization.

While they are museum pieces today, at the time there was a logic to using hard materials for persistence. Even back then, this method wasn’t the fastest way to record information (papyrus was invented at least a millennium before) but it would last and, most importantly, be difficult to alter. Modern technologists still find this approach important — and the efficiency tradeoffs familiar.

Indeed, the goals of documentation haven’t changed much over the last few thousand years. However, as humanity’s most important records are now digital, we are realizing that more than ever we need to find new ways to preserve records and ensure they are immutable.

Threats to data integrity have certainly evolved. Flash drives have a short shelf life (often shorter than papyrus). Authoritarian rulers use social media to sow doubt. Even the human psyche is under attack: Is seeing still believing in the age of generative artificial intelligence?

Evidence has always needed to stand the test of time and the test of scrutiny. Long-established concepts can still help, including decentralization and cryptography (which was likely around even in the days of Suen-nada and Ennum-Ashur). A related modern concept can also help: blockchains.

In the spring of 2022, Russian artillery shells ripped through the walls of several schools in Kharkiv, Ukraine. The whole region was under heavy fire from advancing Russian armed forces, but an intentional attack on civilian targets is a war crime. The United Nations specifically defines education as a human right. Turning sanctuaries of learning into a battlefield creates a vicious cycle of illiteracy and poverty.

There are no statutes of limitations on war crimes. They can be — and mostly are — prosecuted decades later. That means evidence must be preserved. But in an active conflict there is risk of loss, tampering, and damage. While the direct attacks might be top of mind, digital evidence is particularly vulnerable to power grid failures and connectivity changes. If sitting on unmaintained technologies, it can also decay and degrade — think of hard drives failing over time.

Witnesses in Kharkiv shared an instinct with our ancestors from thousands of years ago: to document what happened. Their photos went onto sites like Telegram, but social media isn’t the most reliable place to store critical records. Users can delete their posts or make their accounts private. A platform’s CEO could take down content without any rationale.

Starling Lab set out to authenticate and preserve these vulnerable assets. Co-founded by the Stanford Department of Electrical Engineering and the USC Shoah Foundation, our team explores how web3 technologies and decentralized web principles can be applied in the fields of law, journalism and history. We use open source tools and develop methodologies for the collection and verification of digital evidence.

Our investigators made web archives of social media posts from Kharkiv, verified using state-of-the-art OSINT techniques. Decentralized storage deals preserve the collection on thousands of servers around the world, and the redundant recording of hashes and cryptographic signatures permit trustless inspection of the items and their audit log.

We don’t know what admissibility standards will look like when these incidents have their day in court. But we know that even an untrusted source could produce all the evidence, and prosecutors can quickly verify its authenticity by comparing it to registrations that we made on multiple blockchains.

Open source intelligence (like social media posts) may still be questioned, so Starling arranged for photographers to visit two of the schools. They used the context-rich capture app ProofMode, from the Guardian Project, to include corroborating metadata (including time, GPS coordinates, surrounding cell network, phone locale, etc.). These bundles were cryptographically sealed with the images and their integrity proofs registered to several blockchains for safekeeping.

Starling Lab has since made a pair of submissions to the Office of the Prosecutor at the International Criminal Court, including an analysis of how these methodologies can establish credibility of the evidence.

The challenge isn’t always bringing our technology to a location, but also to a point in time. For a war crimes investigation focused on the Balkans, we authenticated photographs from original 30-year-old film slides.

The same approach – using our Starling Framework of Capture/Store/Verify – has helped us to preserve testimonies of Holocaust survivors (original link no longer available), store thousands of examples of Russian misinformation (original link no longer available), document living conditions for the homeless in California, record promises by politicians about government surveillance, and save examples of climate change impacts in the Amazon.

Cryptography, decentralization, and blockchains are the tools we used to preserve these important records in humanity’s collective memory. These projects have created immutable records to stand up against challenges from the wide-scale adoption of generative AI, sophisticated disinformation campaigns, and changing digital custody practices.

Today’s courts and other civic institutions must confront similar challenges that undermine trust in their own critical records. By embracing similar innovations, there’s a chance for digital evidence to become as resilient as ever – the modern equivalent of being etched in stone.